In a quiet basement of The Mall in Westlands, Nairobi, a hauntingly intimate art exhibition is drawing visitors into a raw, unfiltered confrontation with mental illness, addiction, and survival.

The space, known as Munyu, holds Between the Bars, the first solo exhibition by self-taught multidisciplinary artist Ndung’u Mbithi.

Centrepieces of the show are four woven artworks, crafted from sisal rope and suspended between two rods. Each features the outline of a single chair, painted, looming, and emotionally loaded.

For Ndung’u, the choice of materials is deliberate. Sisal rope is commonly associated with suicide by hanging, and chairs are tragically familiar props in these final acts. These are not just works of art; they are artefacts of his inner battles.

“I begin weaving when suicidal thoughts cloud my mind,” he said softly. “Every knot, every loop, is a meditation. By the time I finish, the darkness has lifted.”

It takes him two to four weeks to complete a piece. The repetition and slowness offer him a kind of therapy, a pathway back to clarity.

He calls the four woven works Chairkicker 1 through Chairkicker 4, a brutally honest reference to what comes just before the end for many people lost to suicide.

This is art born not from theory or technique, but from pain. Last year, Ndung’u tried his hand at weaving for the first time while participating in group exhibitions at the same gallery.

Having started as a volunteer, he learned by simply watching others create. Curator Rose Jepkorir recognised something powerful in his early works and encouraged him to continue.

“I never studied art formally,” he said. “But it became my new love. Curating this show myself was challenging, but also necessary.”

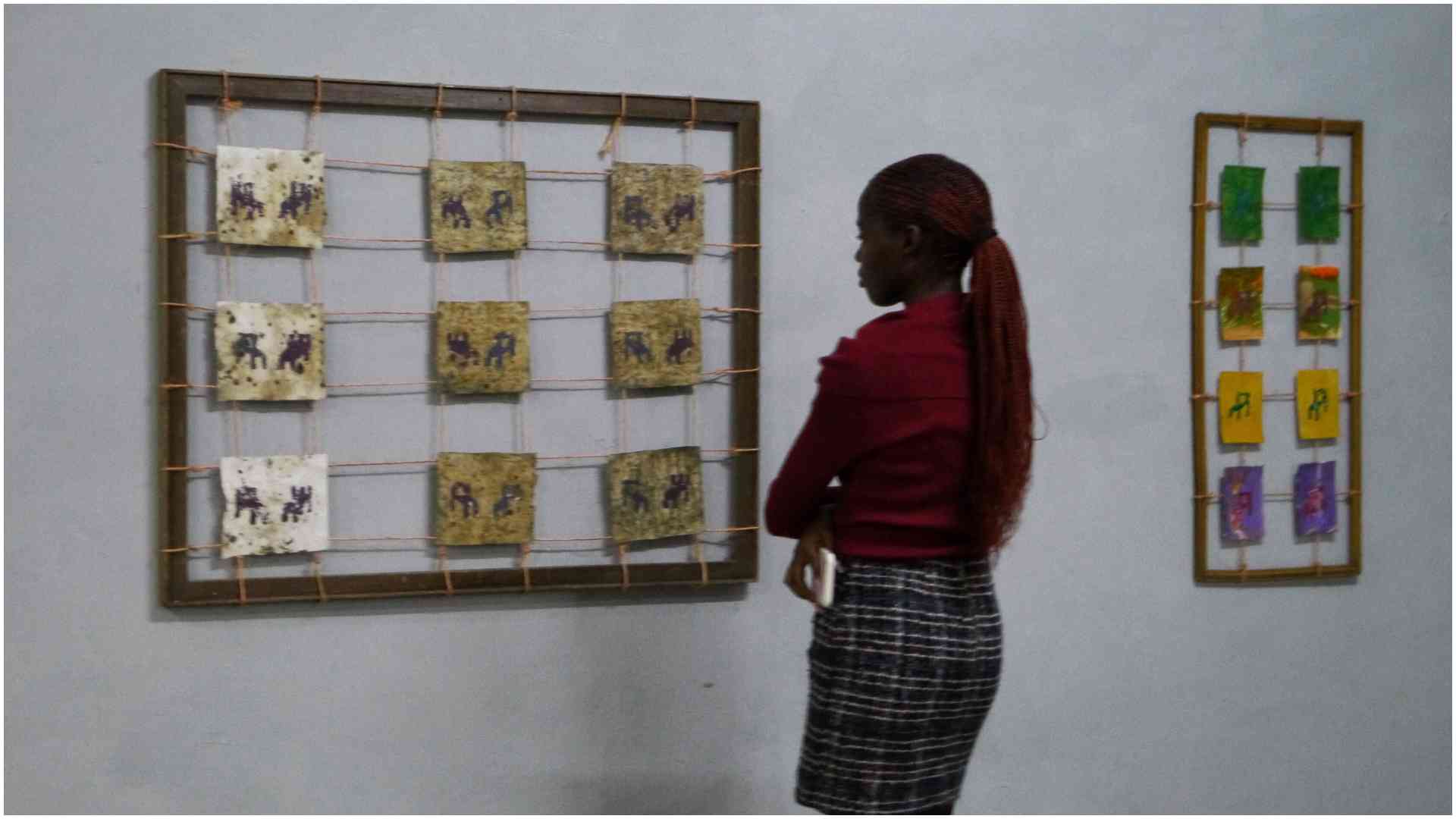

While weaving forms the heart of the show, other pieces extend the emotional landscape. Eight small chair paintings, done on old papers, speak of decay and renewal.

The papers had grown mould while he was away performing in Kisumu, another creative outlet for the artist, who is also a musician.

“I came back and threw them out,” he recalled. “But something told me to take them back, dry them, and paint on them. The mould became part of the work. A mistake turned into meaning.”

There is no symbolism here that isn’t grounded in real life. Displayed nearby are printed pages covered with debt collection messages, reminders of how alcoholism ravaged his finances.

After one particularly bad episode, he was forced to borrow money to make his way home.

At the far end of the gallery stood two installations. One is a stack of chairs in disorder, with ropes descending from the ceiling, visually echoing the sense of chaos and desperation tied to suicide.

The other is a reimagined bar: littered, broken, abandoned. Used cigarettes and empty alcohol bottles are scattered around like relics of self-destruction.

These pieces, like the exhibition title itself, are inspired by Between the Bars, a haunting song by American singer Elliott Smith, who battled addiction and mental illness until his death by apparent suicide in 2003.

Ndung’u sees himself in Smith’s lyrics, in the fleeting comfort of addiction, and in the fight to stay afloat.

“I’ve struggled with alcohol since I was 13,” he reveals. “I’ve been prescribed medication for depression and anxiety. But when I drink, the meds stop working. Sometimes, I black out completely. I’m trying to quit. It’s a very difficult journey.”

He paused, then added, “This exhibition is part of my healing.”

Between the Bars opened on 15 May to coincide with Mental Health Awareness Month and ran until 31 May at Munyu Space. More than just a showcase, it is a deeply personal act of survival, courage, and creative defiance.

Visitors walked away not just having viewed art, but having witnessed a life fiercely held together, strand by strand.