In a thriving democracy, how a government communicates with its people is as important as the policies it implements. Citizens need accurate, timely, and accessible information to stay engaged and informed. That’s what inspired the creation of the Kenya Yearbook Editorial Board (KYEB) in 2007 through Legal Notice No. 187, signed by then President Mwai Kibaki.

Its mandate was to document and publish the government’s milestones, policies, and achievements in a structured and compelling way. The idea was simple yet powerful—build public trust through transparent storytelling and help citizens understand their government better.

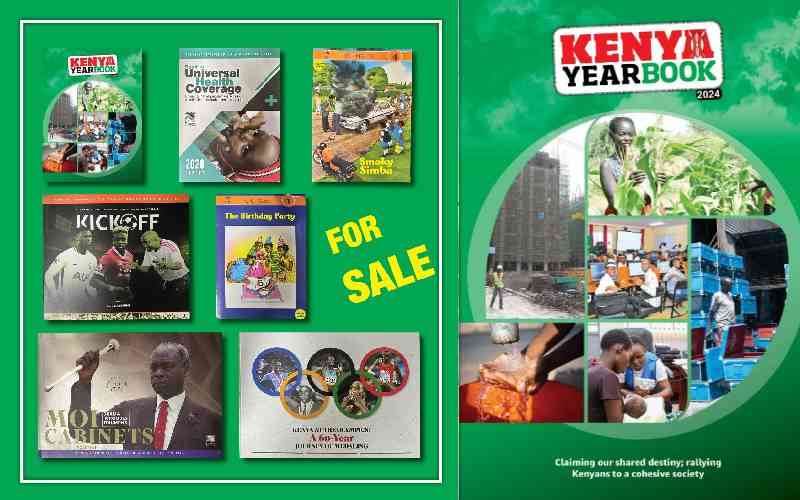

In its early days, KYEB showed promise. The first edition of the Kenya Yearbook was launched on June 28, 2011, presided over by then Vice President Stephen Kalonzo Musyoka. The launch marked a turning point in State communication. It was followed by several sector-focused reports and biographical publications, including Journey of Women Trailblazers and Cabinet Series, which profiled ministers from the Kenyatta, Moi, and Uhuru administrations.

Fast forward to today, and that original vision feels like a distant memory. Despite being well-resourced and having a defined mandate, KYEB has become a case study in institutional drift. More than 15 years since its establishment, the board now appears to have lost its way.

Current and former staff say internal processes are hamstrung by bureaucracy, creativity is suppressed by micromanagement, and professional staff face an environment marked by coercion rather than collaboration.

As a result, content development is sluggish, production timelines are missed, and the final outputs often fail to meet the needs of the intended audiences. The irony is stark: An agency created to showcase progress is now struggling to keep up with it.

Kenya is undergoing rapid transformation. From agricultural modernisation to FinTech innovations, devolution reforms to public digital services, there is no shortage of stories that deserve to be told.

But KYEB has failed to capture this momentum. Its flagship publication—the Kenya Yearbook—no longer commands national attention. It’s often released late and has limited public reach. A digital-first world demands speed, strategy, and adaptability—none of which the Board currently embodies.

To date, the 2024 edition has not been released. Staff at KYEB say it was supposed to be printed and distributed last year, but its compilation was completed only this year and now sits in storage, undistributed.

In theory, this should offer a path for recourse when public institutions underperform. In practice, however, the enforcement of these standards remains inconsistent.

This is not a call for the dismantling of KYEB or changing top management, but a plea for bold, urgent reform. Kenya still needs an agency that can document our national journey with depth, accuracy, and heart. But for KYEB to become that agency, it must reinvent itself.

It needs dynamic leadership, clear performance metrics, and a digital-first communication strategy. It should invest in skilled writers, editors, and visual storytellers who understand both the power of narrative and the urgency of real-time engagement.

It needs to listen to the people it was created to serve—and start telling stories that reflect their lives, hopes, and challenges.

The truth is, Kenya has many stories worth telling. But if we can’t get our own house in order—if an entity created to communicate national achievements cannot itself operate with excellence—then its relevance will continue to fade.

In an age where information is power, State communication cannot be an afterthought. It must be deliberate, dynamic, and inclusive.

The Kenya Yearbook Editorial Board still has a chance to rise to that challenge. Whether it does—or continues on its current path—is a test not just of its leadership, but of how seriously we take public service in this country.

By Clay Muganda