Sometimes in the early 2000, a senior lecturer at Egerton University Joseph Walunywa argued that learners in educational institutions in Kenya should be exposed to nonfiction works as part of their education. Dr Walunywa said that authorities in education could enrich the English language curriculum, which is integrated, to include nonfiction works. The suggestion had persuasive value.

The current English curriculum is tilted towards fictional works. We have a whole paper devoted to fictional works—novels, plays, poetry and oral literature. The curriculum does not provide for nonfiction writing—essays, journals, diaries, letters, biographies, speeches, satires, literary criticism.

This is the reality. Although imaginative works dominate the study of literature in other educational systems, the systems have provided ample room in the English curriculum or language curriculum, for nonfiction works. They are studied and examined with similar rigour as fictional works.

I am afraid. Some teachers of English will cite functional writing in English syllabus as having taken care of the educational value of nonfiction works. There is an attempt to teach some elements of nonfiction in the English curriculum under the 8-4-4 system of education. However, it doesn’t go far enough. It is taught as part of English and not Literature. That is not what Walunywa meant.

Follow The Standard

channel

on WhatsApp

In English, all they teach is the structural aspects of discourse that is defined as functional writing. All teachers do is to define what the various forms of functional writing. It is perfunctory at best. There are no models which students thoroughly study for their artistic values—the things they communicate and how the writers communicate.

In fiction, you have named books of outstanding literary values—what they call set books. You see this in so-called functional writing or, in this case, nonfiction writing. There are no writings of accomplished letter writers, speeches. No landmark reports, memoirs or memos as curriculum materials.

The placement of fictional or functional writing in English as a language has inexcusably limited students’ exposure to the cultural herniate these genres embody. This has denied the students the opportunity to see how writers manipulate language to deal with the issues, problems, challenges and crises that mankind has faced in the past or faces now and in the future.

Studied as literature, nonfiction writings expose students to actual, real named models of discourses by accomplished speakers and writers in the English language. Through this, students get exposed to the finest examples of speeches, letters, reports, as pieces of art. Not as a language and its mechanics—spelling, punctuation marks, parts of speech, etc—but as literature.

This is what the English curriculum was in the old Intermediate school where students sat for the Kenya African Preparatory Examinations (KAPE) in Class eight. The same applied to the English curriculum for secondary education, both under the colonial system of education.

My generation had used these books in Primary education in the 1970s. I joined Class 1 when the books they used under the colonial system of education were still in the primary school libraries at the time.

I also used the textbooks for Literature in English in the old “A” system of education under the 7.4.2.3 system of education. I also used the books in my teaching of English at Kolanya Secondary school in Busia in 1989 and part of 1990.

Suffice it to say that the English curriculum under the dying days of the colonial system of education was much richer than what obtains today. We have, regrettably, confined students—in primary and secondary education—to the study of novels, plays, poetry and oral literature. The ordinary business of life is transacted through literary and rhetorical techniques that you find in great nonfiction works. Organisations don’t transact business through poetry, novels or plays.

This is what Walunywa was saying: Enrich the curriculum with real, named nonfiction works.

He himself had his undergraduate and post-graduate education in the USA. He must have compared and contrasted the English curriculum in basic education schools in Kenya and in the USA.

Literature is any work with outstanding literary merit. The writer or creators of that work encapsulate their thoughts in beautiful or moving language in terms of words. The words could be in prose or verse—in narrative prose or in poetry.

The body of works that define most of literature—be it in English, which is the language of instruction—or the in Kiswahili, is fiction.

In literature, fiction is fabricated and based on the author’s imagination. The work springs from the imaginative powers of the writer. Examples of fiction are short stories, novels, plays, and poetry. It also includes myths, legends, and fairy tales. The defining element is that fictional works are creations of the fertile mind of the writer. Dominant in fiction are plot, settings, and characters. These are the storyline, the time, place, and socioeconomic environment in which a story occurs and the imaginary people who take part in the imagined actions.

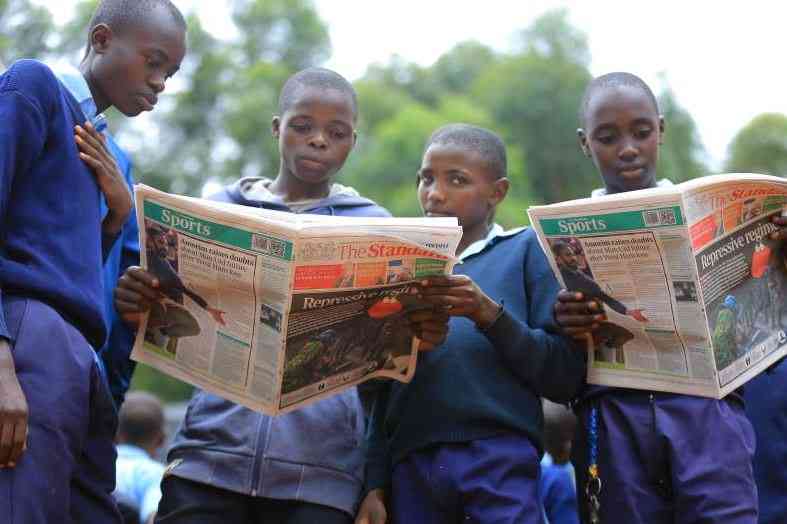

By contrast, a nonfiction work is factual and reports on true events. The raw materials are based on actual events that happened at a particular place and time. Examples of nonfiction works are essays, journals, diaries, letters, histories, biographies, speeches, satires, literary criticism, newspaper articles, and most of the books in the Bible.

Walunywa’s views didn’t find a hearing then. But they still need a hearing, now as they did then.

Follow The Standard

channel

on WhatsApp

By Kennedy Buhere