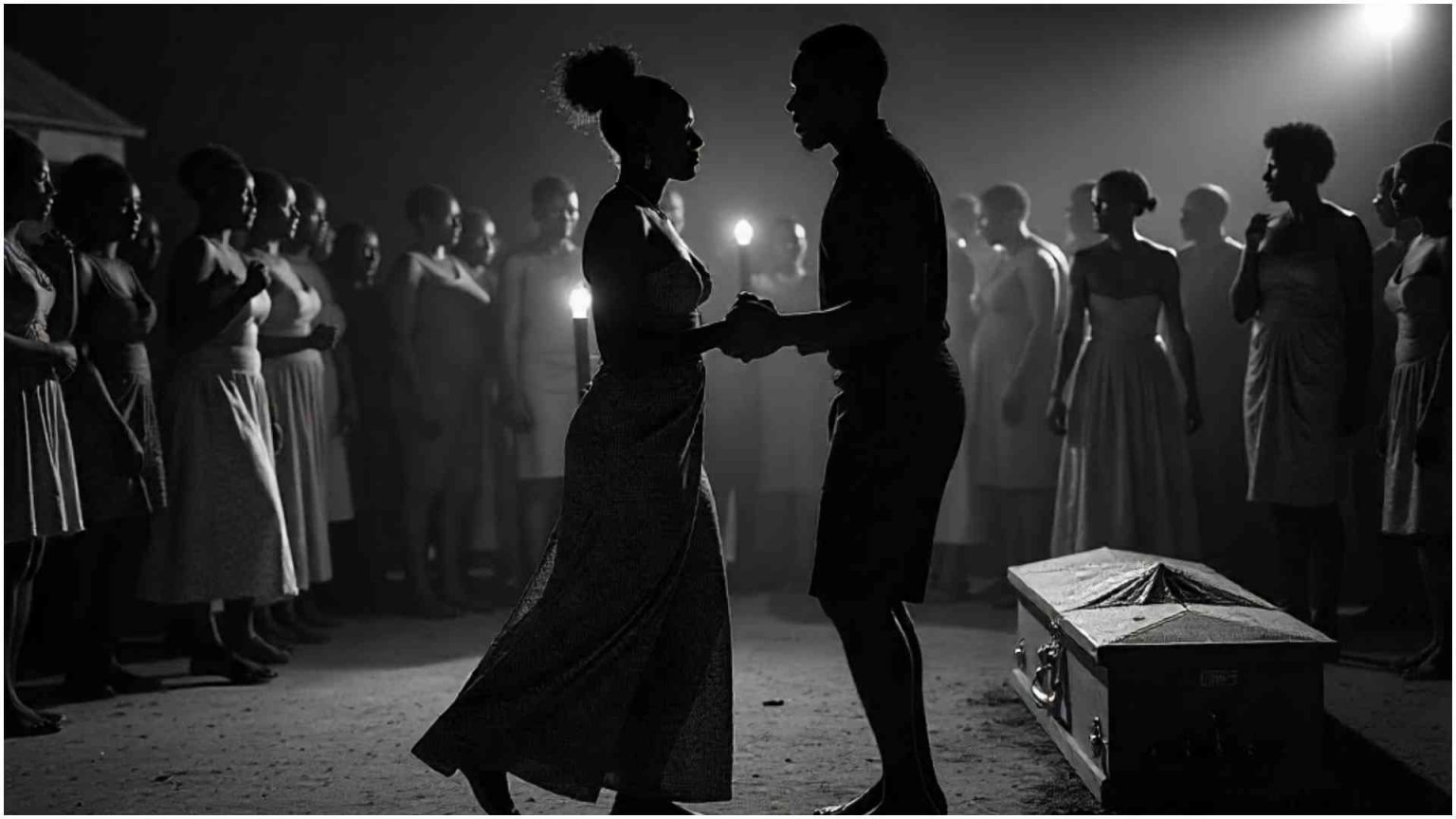

Among the Luhya community of western Kenya, funerals are not merely solemn rites of passage but expansive communal affairs. They draw villages together, weaving grief, solidarity, and ritual into days of mourning that culminate in an event known as disco matanga.

These night vigils once featured restrained music, storytelling, and companionship for the bereaved family. Yet in modern times they have morphed into something quite different: rowdy gatherings marked by thumping music, frenzied dancing, binge drinking, and, increasingly, crime.

To outsiders, disco matanga might appear a curious blending of mourning and revelry. To insiders, it is a cultural mainstay that has endured generations. But as accusations of immorality, lawlessness, and social decay mount, the practice has come under unprecedented scrutiny.

The government now seeks to abolish it altogether, religious leaders denounce it from their pulpits, and communities themselves are deeply divided over whether disco matanga is a ritual worth saving or a tradition whose time has run out.

This clash of perspectives has recently intensified following the intervention of Interior Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen, who has ordered security agencies to enforce a ban on disco matanga across the region.

His directive has ignited a fierce cultural and political storm, pitting government authority and religious conservatism against entrenched tradition and local identity.

Cultural crisis

What began as a practice rooted in communal solidarity has, over the years, become fertile ground for social ills. The vigils are increasingly linked to drug abuse, illicit alcohol, unprotected sex, and criminal activity. Health experts warn of rising cases of sexually transmitted infections and teenage pregnancies. Police, too, associate the gatherings with spikes in burglary, assaults, and even murder.

Interior CS Murkomen minced no words when addressing locals during his recent Jukwaa La Usalama campaign in western Kenya.

“We have had over 100 cases of defilement in the last eight months, and many are highly fuelled by cultural activities such as disco matanga and illicit brew,” he said. “It is a behaviour we must deal with.”

He further argued that the vigils embolden criminals. “Disco matanga has led to an increase in the crime rate. People leave their homes to attend a funeral the whole day and night, giving room for criminals to raid deserted houses,” he said.

Murkomen has instructed police and administrators to ensure the activity is halted once and for all. “Whether it is a funeral or cultural belief that people should have disco matanga at night to give the bereaved families company, our security team should ensure no such activity takes place in the region. Drugs are being abused by young people, there is sexual exploitation, and crimes are committed. This must end,” he declared.

Local resistance

The directive, however, has not gone down well with many locals, who see the move as a direct attack on their heritage.They argue that disco matanga is a practice that has been observed since time immemorial and that they found their ancestors religiously engaging in the ritual. To them, disco matanga is more than revelry; it is an expression of solidarity and a mechanism for raising funds to support the bereaved.

“I am in my late 30s. I was born and found disco matanga in place,” said Evans Wanyonyi from Sirisia in Bungoma County. “The CS has every right to ensure there is no insecurity, but banning disco matanga is a tall order. Among the Bukusu, it is how we stand with bereaved families to make sure they don’t feel lonely in their hours of mourning.”

In Busia County, Moses Walaka shares a similar view. “It is not all about dancing and unthinkable things,” he said. “Disco matanga has been used to attract people so that harambees can be done at night, and money raised to give the deceased a befitting send-off.”

Others insist that the practice, while imperfect, remains a vital tool of social cohesion. Jane Khanaga from Kakamega County believes regulation rather than prohibition is the answer.

“Some chiefs and local administrators are part of the community themselves. They permit the events, yet they are expected to stop them. It will be difficult to ban disco matanga completely. We should instead minimise the criminal elements and restore order,” she said.

For elders, such as Daniel Manda from Busia, disco matanga represents unity, love, and cultural pride.

“There is a sense of togetherness when people come through disco matanga,” he said. “It offers maximum support to the bereaved. The discussion should not be about abolishing it, but about how we can restore its original meaning.”

Others, like boda boda operator Daniel Shikoto from Kakamega, doubt the government will ever succeed.

“Banning disco matanga is like cutting grass. It disappears for a few days, but grows back because the roots remain. Our CS has good intentions, but he should look for another way of curbing crime without eradicating the practice.”

From noble tradition to social vice

Ironically, elders recall a time when disco matanga was both orderly and dignified. Joseph Akidiva of Vihiga County remembers an era when the vigils were governed by strict rules.

“It was not an affair for just anyone. To entertain mourners, you had to be a respectable person. Entertainment was done with a guitar or a drum. People danced in harmony and with discipline,” he said.

Akidiva noted that the vigils even played a role in courtship. “Ladies displayed life skills — cooking, fetching water, making firewood — while men showed responsibility. Some couples met at disco matanga and built families from there.”

Modernity, however, has transformed the ritual. Today, rival youth groups compete violently to control the entertainment. The vigils have been commercialised, with rival organisers clashing over profits.

“We have witnessed fights over women, drugs, and control of events. Some deaths have even occurred,” said Moses Makokha, another elder.

Makokha lamented that what once strengthened families now undermines them. “We have seen drugs and illicit brew, bhang and other substances being sold at night, and nothing is being done. The habit has gone further to the point of young girls and boys engaging in sex, hence a rise in the number of teenage pregnancies and disease infections. These are the reasons why it has become difficult to completely ban disco matanga because it is where youths get relief and solace,” said Makokha.

The church draws a line

Religious leaders have joined the chorus calling for reform, if not outright abolition. In Shianda, Pastor Livingstone Washali of the Council of Churches for Mumias East declared that clergy would boycott funerals where disco matanga takes place.

“Disco matanga has destroyed our youth. It is time the Church takes a stand to protect society,” he thundered at a recent funeral.

Pastor Ruth Nabwire of the Kingdom Restoration Church agreed: “We understand mourning is part of tradition, but it should be dignified. When a funeral turns into an open-air disco, we lose the meaning of paying our last respects.”

Clerics are now urging administrators to limit vigils strictly to a single night, with no entertainment spilling into dawn.

Western Regional Commissioner Irungu Macharia told The Nairobian that security agencies will enforce the ban despite the resistance, threatening to arrest bereaved families, allowing such night vigils.

“As far as matters of security are concerned, what I know is that disco matanga stands banned and we are going to swing into action. Those entertaining it, be it bereaved families or locals will be arrested to ensure the night vigils do not become breeding grounds for criminality, sexual exploitation and drug abuse,” said Macharia.

He warned action will be taken against government officials who will be compromised.

The debate over disco matanga cuts to the heart of a broader dilemma: how should traditional practices adapt in a rapidly changing society? For the Luhya, whose funerals are famously elaborate, the vigils embody more than music and dance — they symbolise solidarity, shared grief, and continuity between the living and the dead.

Yet, as critics argue, when tradition mutates into a vehicle for vice, its legitimacy is undermined. The government’s attempt to intervene reflects a wider struggle between the preservation of cultural heritage and the imperatives of public security and morality.

The question, then, is not only whether disco matanga will survive, but in what form. Some propose regulation: limiting the vigils to one night, banning alcohol sales near funeral grounds, requiring permits, and placing entertainment under supervision of elders. Others advocate outright abolition, insisting the practice is beyond redemption.

What is clear is that disco matanga has reached a crossroads. It stands as both heritage and hazard, cherished ritual and public menace. The resolution of this conflict will not only determine the future of funerals in western Kenya, but also illuminate how a society grapples with the tension between tradition and change.

For now, amid the grief of funerals and the beat of drums, the debate continues — a contest between memory and morality, community and control. Whether the practice will endure, be reformed, or fade into history remains to be seen.

Between the echoes of drumbeats and the stern warnings of authority, the question lingers: is disco matanga a heritage worth saving, or a tradition whose time has passed?