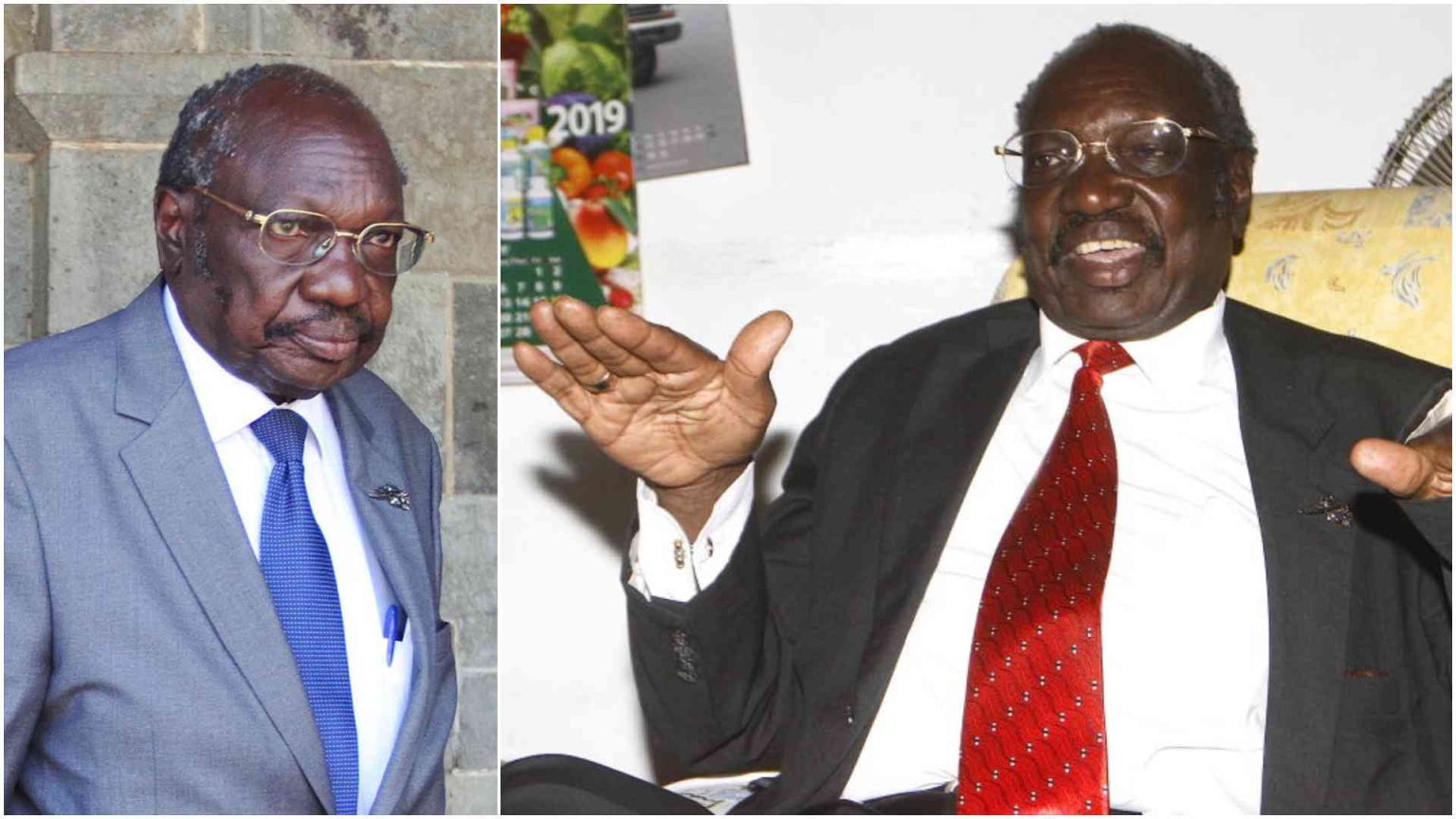

Kenya has lost one of its most polarising scientists, Professor Arthur Obel. At 76, the man who once commanded headlines as a national hero for allegedly finding a cure for HIV/AIDS, died after a prolonged illness, leaving behind a legacy riddled with controversy, scientific disputes, flamboyance, and court battles.

To many, he was a daring researcher who sought to localize solutions during a desperate health crisis. To others, he was an opportunist who capitalized on the desperation of patients to build fame, wealth, and influence.

In the 1980s, as the HIV/AIDS pandemic ravaged Kenya, Obel joined the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) as Chief Research Officer.

It was at Kemri hat Obel first rose to prominence. Alongside Dr Davy Koech, then Kemri Director, Obel introduced Kemron, a supposed wonder drug derived from interferon. The drug was marketed in 1990 as the breakthrough cure for AIDS.

Kemron was sold at Sh74 a tablet, meant to be taken daily for six months. Demand skyrocketed. Patients reported short-term improvements such as weight gain and reduced symptoms, further fueling the frenzy.

Trials in Uganda, the United States, and Europe revealed that Kemron had no proven effect on the HIV virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) dismissed it as an experimental drug. By 1991, Obel resigned from Kemri under heavy criticism, accused of misleading patients.

“The truth got lost in between; it became lies, it became fake,” Dr Koech later lamented. Obel, however, remained unrepentant, insisting Kemron alleviated suffering even if it wasn’t a full cure.

Undeterred by the Kemron fiasco, Obel announced a new drug in the early 1990s: Pearl Omega. He described it as a protease inhibitor capable of reversing HIV-positive status.

The Kenyan government, desperate for solutions, initially supported him. Assistant Health Minister Basil Criticos even tabled Pearl Omega in Parliament in April 1993.

Pearl Omega was sold for Sh30,000 a bottle at the time. Obel claimed seven AIDS patients had regained health after using it. Patients thronged his clinic, desperate for the miracle.

But again, trials revealed no scientific evidence. WHO declared Pearl Omega “herbal” and below international standards. Health Minister Joshua Angatia dismissed it as an illegitimate concoction.

The Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council eventually deregistered him, barring him from practice. He was also sued by patients and the Kenya AIDS Society in 1998 for distributing the drug without approval. Though he won in court, his reputation as a scientist became irreparably tainted.

“Obel was a dreamer who wanted to be Africa’s Louis Pasteur. Unfortunately, he cut corners,” said Prof James Kariuki, a virologist at Kemri.

Beyond the lab, Obel lived a flamboyant lifestyle that drew public attention. He owned 21 high-end cars, including Mercedes Benzes, BMWs, and Peugeots.

A notorious lover of women, he brushed off accusations of womanising with bravado: “Which man does not love women? Tell me, which man can say he does not love women?” he once retorted in an interview.

His lifestyle sometimes landed him in trouble. In 2004, he was accused of shooting at a matatu driver on Tom Mboya Street after being blocked in traffic.

Police found a pistol and 19 bullets in his home, Obel escaped jail after paying a fine of Sh400,000 and damages of Sh100,000.

Critics pointed to his proximity to power. As Chief Scientist in the Office of the President between 1995 and 1999, he had access to State funds and was a close ally of Philip Mbithi, the then Chief Secretary. Observers claimed these connections shielded him from full accountability.

Obel’s controversies extended beyond HIV drugs. He often self-published books with bold titles such as “Curbing the HIV/AIDS Menace Effectively”, “Power and Intrigue”, and “Kenya’s Industrialization Strategy”.

In 2011, long after being disgraced, he published a paper linking WHO clinical staging with CD4 counts in HIV-positive patients at Kenyatta National Hospital. Critics dismissed it as an attempt to regain credibility.

Still, he never lost his knack for dramatic claims. In 2019, he was said to be selling a new drug called Iconaire, which he claimed boosted CD4 counts in HIV patients. At Sh30,000 per dose, Iconaire stirred fears of another Pearl Omega-like saga. Obel insisted it was not a cure but merely a supportive therapy.

Public opinion on Obel remained split. Many patients who had briefly regained strength after taking his drugs defended him. Others accused him of preying on desperation.

Professor Arthur Obel lived as he died, shrouded in contradiction. A brilliant mind who pursued bold ideas, but one whose methods, lifestyle, and defiance cast long shadows on his achievements.