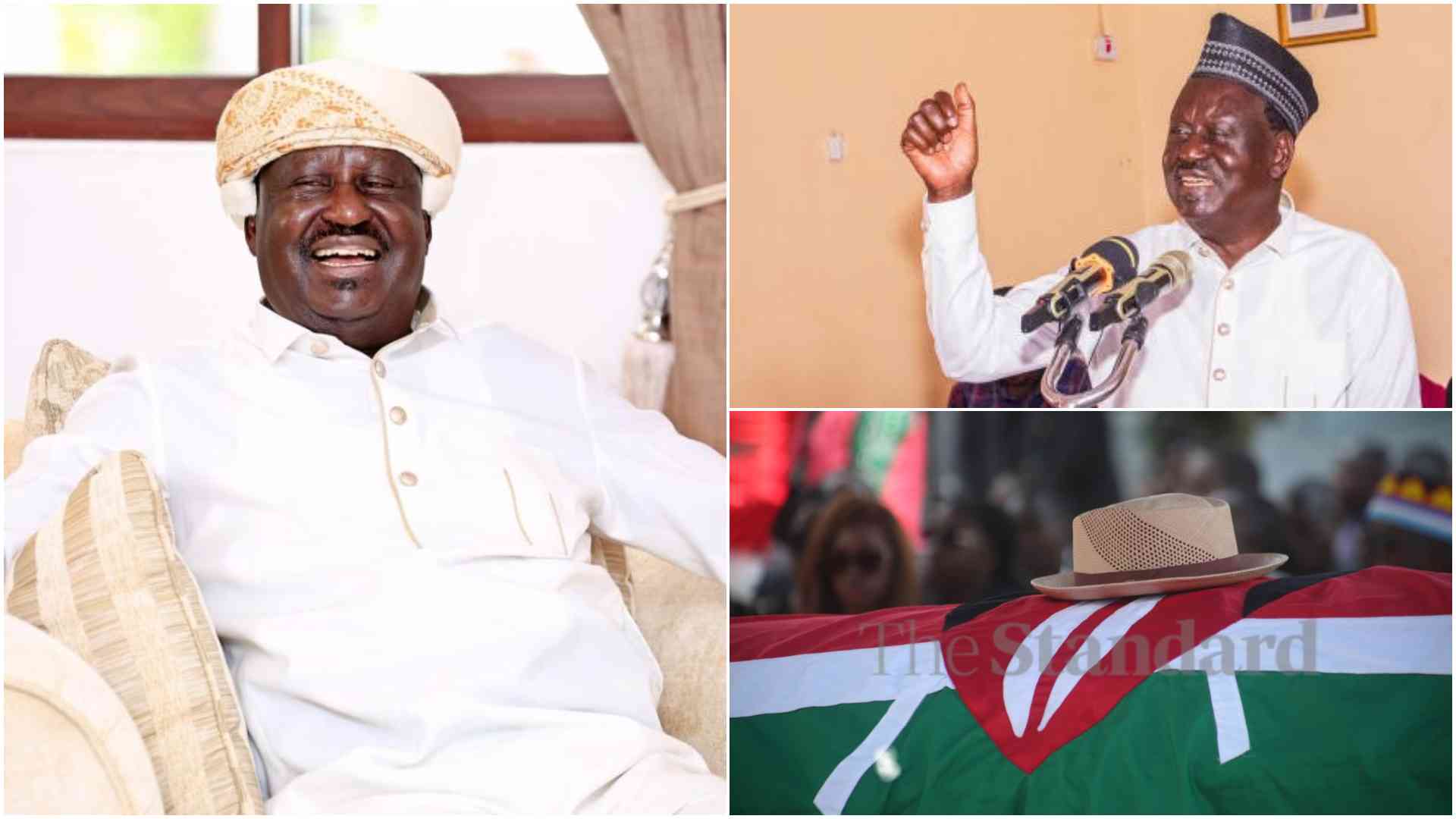

When the drums of ohangla began to roll and the voices of Luo music stars Prince Indah, Musa Jakadala and Elisha Toto rose in harmony, it was not for a campaign rally this time. It was a farewell symphony — a nation’s musical send-off for Raila Amollo Odinga, the man they called Baba, Tinga, Agwambo, the people’s president.

From Kisumu’s Jomo Kenyatta Stadium to Nairobi’s Nyayo Stadium, Kenyans lifted their voices one last time for the leader whose name had echoed through decades of struggle and song.

“Chunya winjo ka pek, woyo tama, muya rumo na! Apenji, kara iwewa gi ng’awaaa?” which translates to, “My heart is heavy, I am speechless, I cannot breathe. I ask you, whom have you left us with?” is a question posed by Prince Indah in his tribute, something many are asking.

The same rhythms that once fuelled Raila’s marches for justice now carried him to his final rest. As choirs swayed and tears fell, one truth rang clear: Kenya’s political story had always been sung to the rhythm of Raila Odinga’s name.

Since his passing on October 15, music has become the nation’s language of grief. Artists across Kenya and East Africa did what they knew best — they sang.

From gospel choirs to ohangla drummers, from studio recordings to street performances, every note carried the weight of farewell. Some sang in pain, others in gratitude, but all in honour. It was as though every melody whispered, “Thank you, Baba.”

Collective balm

Bahati, who once shared a campaign stage with Raila, was among the first to release a tribute. His song “Bye Bye Baba” begins with Raila’s own voice echoing through a cheering crowd, followed by Bahati’s trembling refrain: “You taught us to believe, you showed us the way.”

The accompanying video — filled with nostalgic clips of Raila dancing, laughing and waving at supporters — spread rapidly across social media. Soft, soulful and sincere, it became the song of the moment, a collective balm for a grieving people.

From Tanzania came more musical farewells. Gospel star Christina Shusho, her voice gentle yet resolute, released “Pumzika Baba”, calling Raila a reformer and a father of freedom. “We loved him, but God loved him more,” she sang in Kiswahili — a line that settled over mourning crowds like a prayer.

Fellow Tanzanian artist Rayvanny added his voice with “Bye Bye Raila Odinga”, a song that spoke not just of Kenya’s loss but of Africa’s sorrow.

“Africa is crying for Baba,” Shusho said — and indeed, the continent mourned with Kenya.

Back home in Luo Nyanza, the music flowed like a river returning to its source. It was here that Raila was born, and where his spirit had always felt most at home.

The ohangla drums beat deep and slow as artists such as Prince Indah, Musa Jakadala and Elisha Toto released emotional tributes in Dholuo, each hailing him as Wuod Oganda Amolo — the son of the people.

Their songs told of a man who carried the nation’s hopes, who fought for justice, and who never surrendered the dream of a fairer Kenya. In bars, buses and churches, the tracks played on repeat, mixing mourning with memory.

Even in death, Raila brought people together through music. His favourite tune, “Jamaican Farewell”, played softly at his send-off, its lyrics of parting and remembrance perfectly fitting the moment.

Unbwogable

It was a gentle goodbye for a man who once made millions chant “Bado Mapambano” — “The struggle continues.” Only this time, the struggle was over, and the nation was saying thank you.

For Raila, music was never mere entertainment. It was a bridge — a language of connection between him and the people. Long before his final tributes, his life had danced to the beat of Kenyan politics.

From “Unbwogable” to “Leo ni Leo”, Raila’s political journey was told through songs that united crowds and stirred hope.

In the early 2000s, before streaming and viral videos, matatus and market stalls across Nyanza played Onyi Papa Jey’s Raila ODM. It became a local anthem, praising the son of Jaramogi as a champion of the people.

Around the same time, Unbwogable by Gidi Gidi Maji Maji became a national battle cry during the 2002 elections. Its message of courage and resilience perfectly matched Raila’s own rallying spirit. Wherever he went, crowds roared “Unbwogable!” and he would lift his hand in salute, smiling wide.

Then came “Bado Mapambano”—more than just a song, it became Raila’s slogan of hope. It echoed through protests, campaigns, and streets. It was sung by mothers selling vegetables and by students marching for reform.

For many Kenyans, “Bado Mapambano” was Raila himself—the voice that reminded them never to give up, even when the fight was hard.

Onyi Papa J then brought the popular ODM in 2007, an anthem that not only swayed voters but also became the party’s anthem. NASA Tibim by Onyi Jalamo followed in 2012, a melody that got his supporters dancing in every rally.

When the 2022 elections approached, Raila once again turned to music—not just as inspiration, but as participation.

He teamed up with western Kenya musician Emmanuel Musindi to record “Leo ni Leo”. Borrowing the catchy chorus from Musindi’s original song, Raila added his own words of hope: “Inawezekana”—It is possible.

The video showed him singing, smiling, and dancing with young supporters, proving that even after years in politics, he still understood the power of rhythm and connection. The song spread fast, becoming both a campaign anthem and a celebration of belief.

Bahati soon joined in, releasing “Fire”, a lively campaign song featuring Raila himself. Later, Ben Githae—who had once sung “Tano Tena” for a rival party—switched sides and recorded “We Are Safe with Baba and Mother Karua”, praising Raila and his running mate Martha Karua as a team of change.

During that election season, every rally felt like a concert. Music was not just background entertainment; it was part of the message. It made politics feel alive, personal, and hopeful.

Nation’s soundtrack

And that was Raila’s gift—he understood how deeply Kenyans felt music. He knew that a song could reach hearts where speeches could not. Whether standing on a rally truck in Kibera or dancing to ohangla in Kisumu, he always seemed to find the rhythm. People sang because of him, and with him. His name became part of the nation’s soundtrack.

That is why, when he died, it was music that carried the news. The same voices that had once shouted his name in victory now whispered it in sorrow.

From radio shows to TikTok videos, every platform became a stage for remembrance. Young artistes who had never met him sang about his courage.

Older ones who had known him personally wrote songs filled with both loss and pride.

The melodies were soft, but their message was strong: Baba’s journey had ended, but his music would live on.

In Nairobi, Ruth Mbithe’s gospel tune “Lala Salama Raila Odinga” brought comfort to many. Her gentle voice urged Kenyans to let him rest in peace. “Sleep well, Baba,” she sang, and many wept.

Vinny Flava added “Agwambo”, blending modern beats with heartfelt lyrics about leadership, love, and legacy. In Kisumu, crowds gathered by the lake to dance and cry to the rhythm of ohangla bands playing through the night. Every drumbeat seemed to echo his famous words: Inawezekana—It is possible.

Even at his funeral, music led the way. Choirs sang hymns in Kiswahili and Dholuo. Politicians, friends, and family swayed to the rhythms that had followed him through life.

Raila Odinga was the leader who danced with his people, who sang of freedom, who turned rallies into concerts and protests into choirs. He proved that politics could have a beat, that hope could have a chorus.

Now, as the music fades and the dust settles, Kenya must face its tomorrows without the man whose voice defined so many yesterdays. Yet, his presence lingers — in the chants of “Unbwogable,” in the defiant echo of “Bado Mapambano,” and in the quiet faith of “Inawezekana.”

They are not just songs. They are memories — verses of a nation’s long, unfinished ballad.

For Raila Amollo Odinga, politics was poetry set to music. His story, written in rhythm and melody, will not end with silence.

Because somewhere, in the hum of an old radio, the chorus still plays: “Bado Mapambano.” And Kenya still listens.