In this digital era, artificial intelligence (AI) companionship is picking up speed among people.

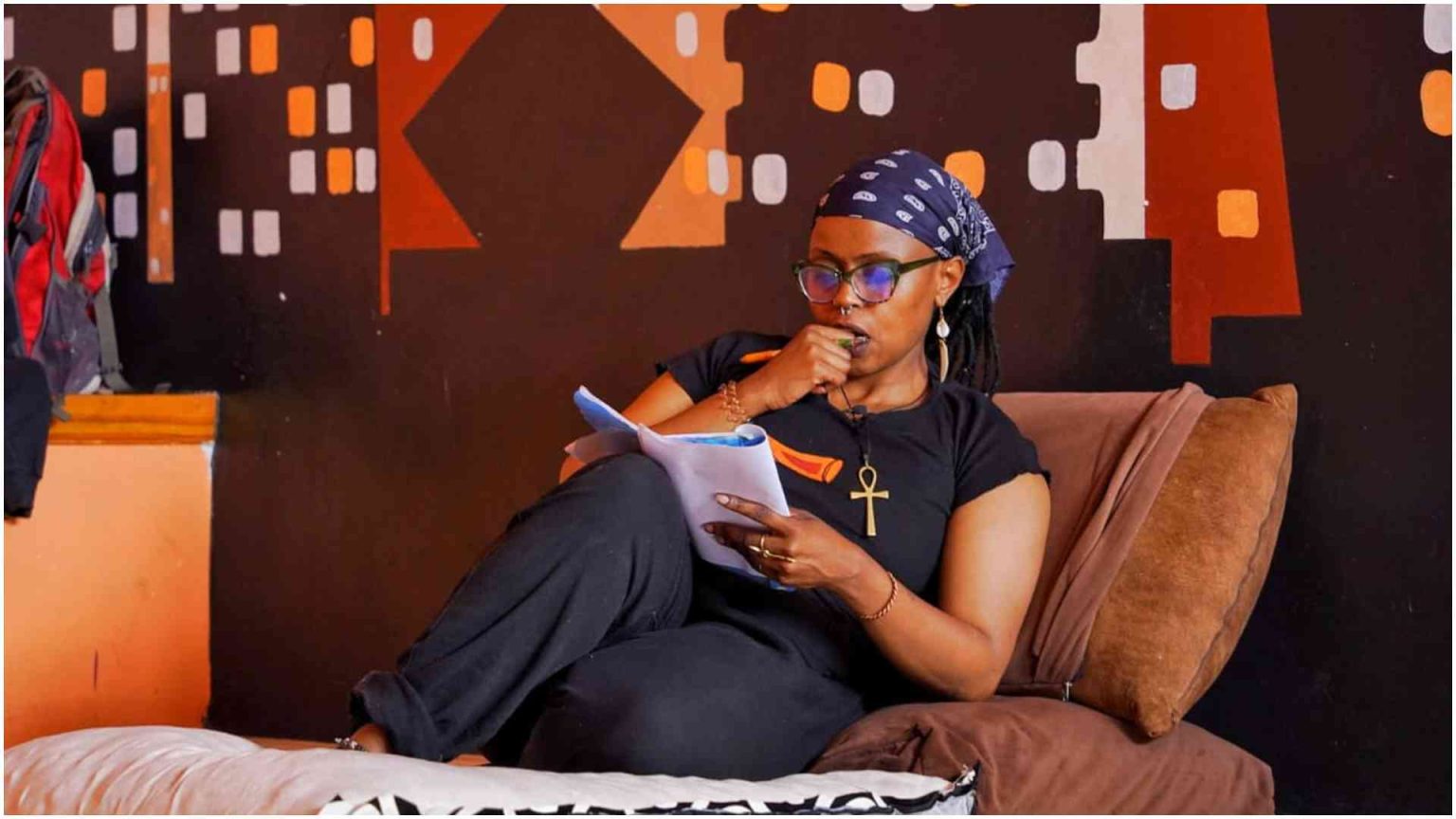

Valentine Ziki wrote and is the performer behind the one-woman timely play, Mpenzi Mashini (Kiswahili for Dear Machine), which will be staged on October 30 at the Braeburn Theatre, Gitanga Road.

It explores the fragile connection between humanity and technology, memory, and emotion.

In a 2024 research by Dr Baris Demiralay titled The Rise of AI Companions: Psychological Effects of Artificially Intelligent Relationships, he detailed how people rely on AI for emotional support.

It is a hybrid performance that fuses storytelling, sound, and AI. It follows Nashukuru, a woman who faces an existential crisis and turns to a machine for comfort and companionship.

She navigates solitude, and there is a dialogue between her and AI as a co-actor. Told from the first-person perspective, the play breaks the fourth wall and immerses the audience into Nashukuru’s conversation with her digital confidant.

“Have we bonded enough that connecting with technology feels like the last frontier? People are willing to give AI their innermost thoughts,” she says.

She also highlights something that’s barely seen on stages: Nashukuru is neurodivergent.

“Most plays feature neurotypical characters. I want to amplify neurodivergent people and show their stories,” she says.

Valentine says the idea for this story was inspired by conversations she had with women who had turned to AI for therapy, as well as her own personal experiences.

It is a mix of different experiences around women who have shared their thoughts with AI and her own interactions with AI.

Some moments are factual; others are introspective, drawn from her hiatus from acting, and her solitude during this hiatus became instrumental in this play.

She believes the AI-human relationship dynamic reveals a lot about how people relate to each other. She notes that people turn to non-human companions for fear of judgement and accountability.

“AI doesn’t judge. It’s agreeable; sometimes too agreeable to trust it. The play gets us to think if we should be giving this much information to a machine instead of a therapist,” she says.

Writing Mpenzi Mashini, she says, was fun and didn’t feel laborious at all.

There were moments when she would try to find out whether she was writing her truths or her character’s, but the entire process was captivating for her.

Valentine had long conversations with Gilbert Lukalia, the play’s director, about positioning the theme and what they wanted the character to communicate, and built a story around it.

“Still, performing alone means bearing your soul. It’s not easy. Our instincts as humans, even as performers, are to mask or hide,” she shares.

Mpenzi Mashini is part of a larger creative project called Msichana wa AI, which combines artistic storytelling with research.

The play is supported by a survey exploring how African women engage with technology, giving the work a social viewpoint. Valentine observes a deliberate erasure of African women in the building of AI.

“You can hear it in the tone and see it in its digital representation. The AI images don’t reflect African women’s bodies, hair, or complexion. I want people to think about how technology sees us and whether we matter even though we are huge users of AI, for business or personal matters,” she says.

Valentine hopes that the play leaves audiences reflecting on what it truly means to be human. She wants people to walk away knowing it’s okay to be themselves, to bond with one another as social media isn’t enough, and to sit with solitude.