Navels come in all manner of shapes influenced by how the umbilical cord was cut, the healing process, body structure, and other factors such as body fat and abdominal wall structure.

When most people stare at their belly button, they never

care if it is situated too high or too low on the abdomen. But plastic surgeons

do. They use something called the golden ratio – a number around 1.62, believed

for years to represent ‘perfect’ natural proportions.

In cosmetic surgery, if the distance from your chest bone to

your belly button (navel), compared to the distance from your navel to the

lower part of your tummy, is close to that number, doctors say the abdomen

looks nicely balanced.

Turns out Kenyans, especially men, are different.

Plastic surgeons at the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH)

made an unusual request to examine the belly buttons of patients, hospital

staff, students, and even visiting family members of inpatients, between

November 2023 and January 2024.

The 411 adults who agreed (62 per cent men) were aged 18-65

years. They signed consent forms and were led to a private examination room at

the hospital, in the presence of a nurse and a companion of their choice.

Participants lay on their backs during the examination.

The results could change how plastic surgeries are done in

Kenya.

The surgeons found that Kenyan belly buttons tend to sit

slightly lower on the abdomen than international averages. The average Kenyan

umbilical ratio is 1.69, not the global 1.62. Men showed a higher ratio of

1.74, which means their navels were positioned notably lower, while women

averaged 1.62, almost perfectly matching the classic golden ratio. Body weight

also played a role — individuals with higher BMI tended to have belly buttons

positioned slightly higher on the abdomen.

The results were published last week in the Journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, in a paper titled, “Defining Umbilical

Norms in Kenya: A Morphometric Analysis of 411 Adults.” This groundbreaking

study is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa. It was led by Dr Sama

Fofung, a plastic, reconstructive, and aesthetic surgeon at KNH.

Dr Benjamin Wabwire, KNH’s head of plastic and

reconstructive surgery, and Dr Joseph Wanjeri, a plastic surgeon and a lecturer

in the Department of Surgery at the University of Nairobi, also took part in

the study.

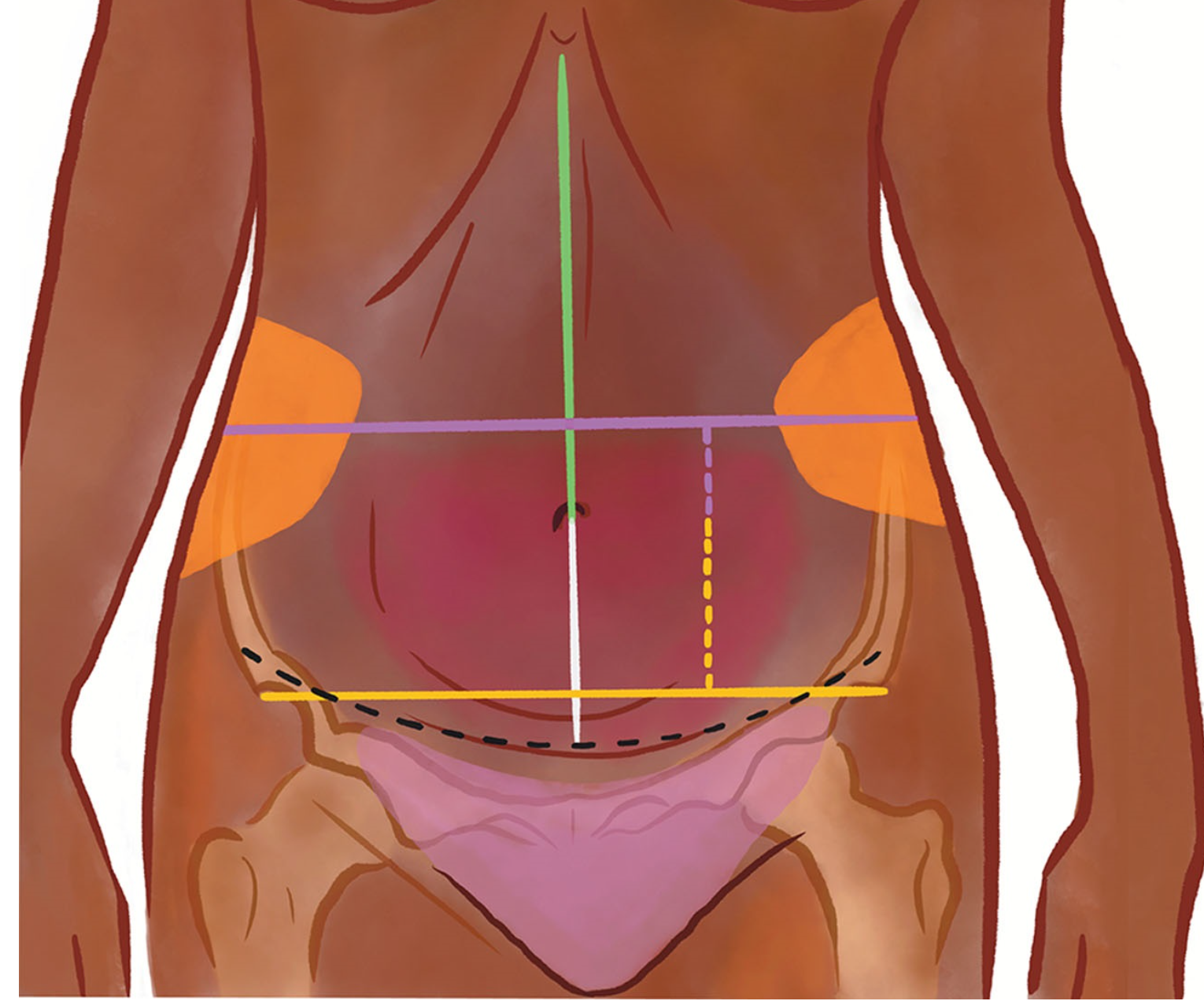

The surgeons explained why the findings are important in

their work: “Surgical procedures involving the umbilicus—such as

abdominoplasty, umbilicoplasty, hernia repair, and body contouring after

massive weight loss—rely on accurate, culturally appropriate references for

umbilical location and shape.”

One intriguing discovery is that some Kenyans still prefer

the golden ratio visually, even though their bodies do not follow it. The

authors write: “Kenyan participants sometimes still favor 1.62 in side-by-side

image comparisons—pointing to a divergence between the actual local ratio and

individuals’ subjective aesthetic judgments.” They describe this as a classic

cosmetic dilemma: “‘what we have’ versus ‘what we want’ can differ.”

The authors believe plastic and reconstructive surgeons

should now start using Kenyan measurements, not imported ones. They propose a

formula: “For abdominoplasty or isolated umbilicoplasty in Kenyan and similar

East African patients, beginning with an X:U target of approximately 1.69—then

fine-tuning by −0.03 per BMI unit and +0.10 for male sex—should recreate a

position that aligns with local anatomical norms.”

They added: “These population-specific metrics provide

Kenyan surgeons with a numeric and morphological template for anatomically

precise abdominoplasty and umbilicoplasty.”

Another surprise of the study was the belly button shape. Now,

navels come in all manner of shapes influenced by how the umbilical cord was

cut, the healing process, body structure, and other factors such as body fat

and abdominal wall structure.

But if your navel is not oval, you are an exception. The

authors reported: “The oval contour was overall most common (49.6 per cent)

followed by distorted/protruded (19.0 per cent), T-shaped (15.1 per cent),

horizontal (11.2 per cent), and vertical (5.1 per cent).”

Kenyan men had even stronger dominance of the oval shape.

“Two-thirds of men have oval umbilici, versus a more diverse pattern in women,”

the authors said.

The participants were also asked if they favoured specific

umbilical shapes, such as oval, vertical, or T-shaped.

The vertical navel shape emerged as the most popular,

aligning with several Western studies that identify vertically oriented navels

as aesthetically appealing.