Audio By Vocalize

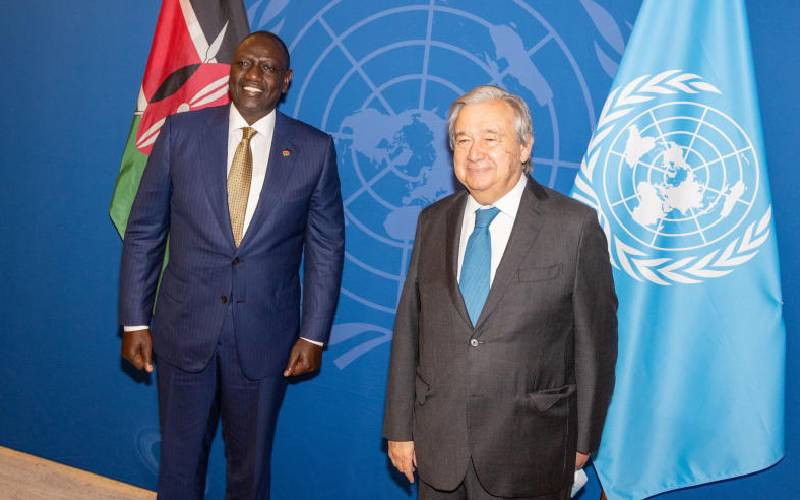

President William Ruto and United Nations Secretary General António Guterres in New York, USA, on September 21, 2022. [File, Standard]

As global order strains and multilateral institutions falter, Africa cannot afford absence from the United Nations Secretary-General race. Contesting the office is not about entitlement or symbolism. It is about refusing to be discounted in a world being reshaped in real time.

This is not a season for lowered eyes or hesitant steps. History does not pause when the world tightens its grip, it accelerates. In moments of global uncertainty, some retreat and others hesitate. Africa should do neither. For Africa, and for countries such as Kenya that have long invested in multilateral engagement, this is not a moment to step back from the global stage. It is a moment to step forward and contest.

The case for contesting the United Nations Secretary-General post does not begin with the office itself. It begins with a harder truth about power. In global systems, absence is read as incapacity. Silence is treated as consent. When no African contender enters the race, the signal received is not caution or humility, but irrelevance. Running matters not only to win, but to establish presence, credibility and refusal to be pre-excluded.

Africa understands leadership under constraint. Across the continent, authority has long been exercised amid overlapping crises, fragile coalitions, contested legitimacy and external pressure. Decisions are made under scarcity, not abundance. Influence is negotiated rather than assumed. These conditions are not weaknesses. They are training grounds for the kind of leadership a fragmented global system increasingly requires.

Sustained engagement

Kenya’s diplomatic record reflects this reality. From mediation efforts in the Horn of Africa to sustained engagement within the African Union and the United Nations system, Kenyan diplomacy has relied on convening, bridge-building and persistence rather than coercion. This is not accidental. It is the product of operating in environments where stability depends on patience, sequencing and keeping dialogue alive even when outcomes were uncertain.

It is from this experience that the case for Africa contesting the Secretary-General race must be understood. Not as a claim to entitlement, but as a refusal to internalise global hesitation. Contesting is how relevance is asserted. It is how credibility is maintained. It is how Africa signals that it is not merely an object of global management, but a contributor to global stewardship.

Only after this point does the nature of the office itself come into view.

The United Nations Secretary-General is the most burdened role in global governance. When wars stall, humanitarian systems falter, diplomacy thins and norms erode, attention turns to that one role. Expectations gather quickly. Outcomes are demanded without consensus. The office is asked to steady a world that no longer moves together or agrees on direction. When results fall short, disappointment follows, often framed as failure.

Yet the Secretary-General was never designed as an executive authority directing outcomes across a divided international system. The role was shaped to stabilise rather than command, to warn rather than enforce, and to preserve space for cooperation when power hardens and communication fails. Over time, restraint has been misread as absence. A stabilising function has been recast as executive leadership. The problem is not lack of power, but misaligned expectation. This is what makes the office appear impossible.

The office does not command armies, control borders or allocate sovereign resources. Its authority flows from persuasion, legitimacy and consent among member states whose interests often diverge sharply. It operates by convening, signalling, sequencing and warning, bringing actors into the same room, framing choices and keeping fragile channels open when others have given up. These tools are easily mistaken for weakness, yet they are often the last lines of stability.

Paradoxically, this is why African leadership belongs in the contest.

The skills required to make the office function are not those of command, but of endurance. Not dominance, but calibration. Not spectacle, but continuity. These are lived experiences across much of Africa’s political landscape: leadership under pressure, governance amid fragmentation, stability without illusion.

There is a growing temptation, as cultural anxiety and political retrenchment spread globally, to read rising exclusion as a signal to withdraw. Migration debates harden. Diversity itself becomes contested. In such moments, some argue that this is not the time for African leadership to push forward. That reading is mistaken. Periods of contraction do not reward retreat. They reward steadiness.

Contest does not mean triumph. It means presence. A race entered is a position asserted. A race avoided is a position surrendered. Even without victory, contesting signals that Africa will not be discounted by default.

Multilateralism does not fail because it lacks force. It fails when roles lose meaning and expectations drift beyond design. As the global system tightens under pressure, this is not the moment for Africa to wait for permission. It is the moment to insist on relevance.

The office may appear impossible. But impossibility is not a reason to retreat. For Africa, and for Kenya, it is a reason to step forward and contest.

Ambassador Awale Kullane is an expert in governance, leadership and diplomacy.

Follow The Standard

channel

on WhatsApp

By Awale Kullane