Sitting behind an ornate desk on the second floor of the Kenya National Archives and Documentation Services building in Nairobi, Francis Mwangi is a satisfied man.

As the institution’s director, Mwangi has overseen one of the most tumultuous journeys to have some of Kenya’s most treasured historical records repatriated back to the country from the United Kingdom.

Last week, the UK government handed over modern digital equipment that will assist the Kenyan government in accessing over 300,000 colonial-era documents that had been received in December 2024.

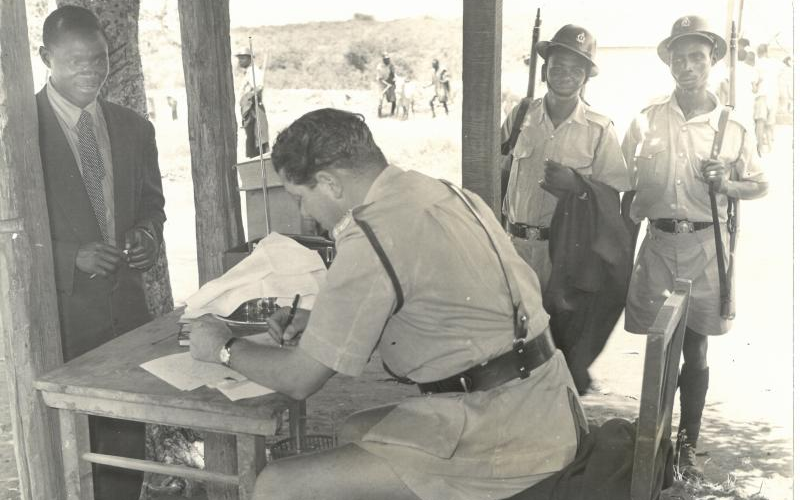

The documents were taken away on the eve of Kenya’s independence so that the government of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II would not be incriminated for atrocities committed against the Kenyan people.

Since then, Mwangi has been guarding the digital components containing raw files of the documents with his life.

“I am guarding it with my life. I have a team that is working on the final touches to determine how Kenyans will access the documents.”

The 60-year journey to have these documents released back to Kenya has been an arduous one. The clamour to have them repatriated began shortly after independence in 1964, when the new Parliament started to work on the Public Archives and Documentation Act.

A key clause in the Act required the director in charge of the Kenya National Archives to get the documents back.

The clause said the director shall “take such steps as may be necessary to acquire and have returned to Kenya any public records or records of historical value to Kenya which may have been exported before the commencement of this Act”.

In 1967, the government followed up by forming an inter-ministerial committee to have documents come back. Over the years that followed, the UK government resisted calls to have such records returned to Kenya, arguing they were the property of the British government.

Kenya exerted more pressure by sending officers to London in a bid to get copies of these records.

“We got some microfilmed records during the Mau Mau case against the British that was instituted against the UK government in 2009. The Mau Mau legal team needed to have some of the records for reference during the case. Apparently, some of these records were stored in a high-security installation, so you can imagine the challenges of wrestling them from such a place,” Mwangi said.

Hanslope Park was described as “the fortress-like warehouse for top-secret government files,” and the documents here were never made public.

The place has a long history, especially that relating to World War II. Britain’s radio security service was based here, and so were the speech “scrabbling” operations during the war.

During the Mau Mau case, the world got a glimpse of the secrets that lay in Hanslope Park, especially those relating to atrocities committed against the Mau Mau fighters.

One such document used in court, dated 17 January 1955 and labelled ‘TOP SECRET’ shows how one District Officer was accused of “murder by beating up and roasting alive of one African in a Home Guard Post”.

Interestingly, the telegram to the Secretary of State recommended that the eight Europeans charged with those crimes be granted immunity from prosecution under a new set of rules.

Other documents relate to the deplorable conditions within the so-called ‘screening camps’ where the colonial government sought to break the will of Kenyans deemed to be sympathetic to the Mau Mau cause.

Another transmission by A. Young, who had been sent to Kenya to oversee the police, said “the horror of the so-called screening camps, which, in my judgement, now present a state of affairs so deplorable that they should be investigated without delay”.

Given the gravity of such accusations against its officers, it is not a surprise that the colonial administration and successive governments were unwilling to release these documents for fear of being held responsible.

In 2013, Mwangi and his team visited Hanslope Park, where the UK government promised, albeit reluctantly, to digitize some records. “We clearly told them that their right to have the documents in the UK was over,” he says. The records under file FCO 141 were later stored at The National Archives in London.

Undeterred, Mwangi made another pivotal trip to Australia in June 2017, where he articulated his quest for Britain to return these materials with the global head of the International Council of Archives.

“I made more noise to the overall boss who said the UK has agreed to give us digital copies of these records at their cost. That was a win for us. In any case the head of the archives in the UK was leaving office in 2023 and did not want to go before we got these records,” says Mwangi.

Finally, in December 2024, UK High Commissioner to Kenya Neil Wigan handed over the digitised archival material relating to the Mau Mau era and intelligence relating to Kenya’s nationalists who were in the forefront of agitating for independence.

Does Mwangi now believe Kenya has all the records it was clamouring for?

“I will only confirm that once we open all the documents and compare with the listicle I saw in London,” he says.

“Remember there were attempts to alter Kenya’s history by redacting some portions that incriminate the British in the atrocities.”