Kenya’s highways may be expanding at record speed, but travellers say the journey remains unsafe and undignified.

With over 4,600 deaths recorded on the roads annually and billions lost to inefficiencies, the absence of rest areas, toilets, eateries, and safe parking bays has turned long-distance travel into a public health and safety crisis.

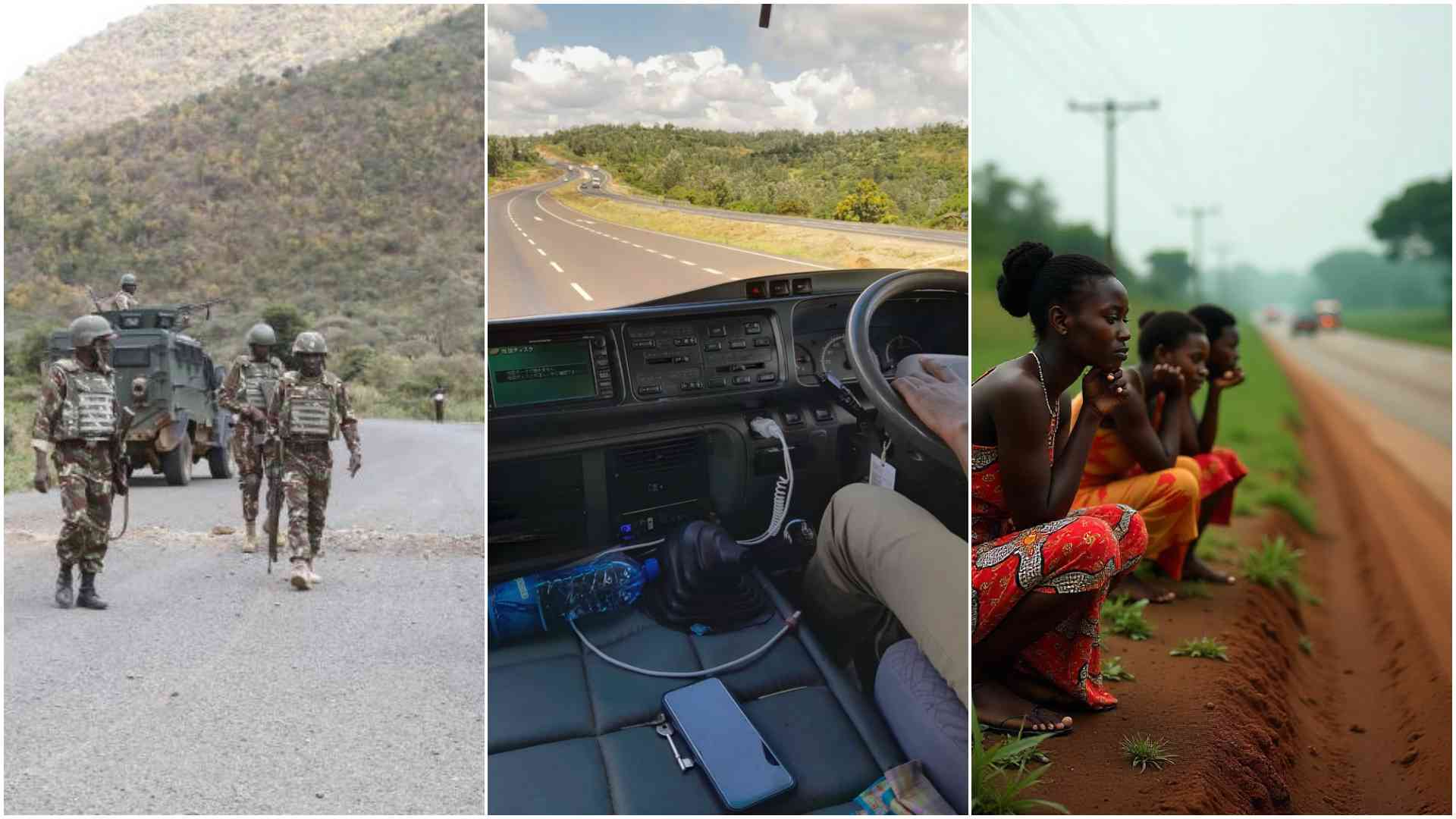

On a scorching afternoon along the Isiolo–Nairobi highway, a bus slows down near a roadside. Passengers spill out, some looking for bushes to relieve themselves, others stretching in the open sun with no shade in sight. It is a common scene across Kenya’s highways.

For many travelers, the absence of rest areas, toilets, eateries, and safe parking bays is more than an inconvenience. It is a public health and safety crisis.

Drivers battle fatigue without proper stops, families struggle with emergencies in the middle of nowhere, and long-distance truckers are forced to sleep on unsafe road shoulders, exposing themselves to accidents and banditry. The problem is particularly dire in northern Kenya, where insecurity and poor services make road travel a gamble.

Gerad Kimani, a driver with Inana Sacco, has spent years ferrying passengers on the Isiolo–Nairobi route, but every trip brings the same challenge.

“We have challenges. We are forced to go to hotels and since we are not buying, they may decline to help us. When it rains, it becomes worse,” he says.

His passengers, many of them traveling long hours, often plead for a stop, but there is no public washroom, no designated rest bay, no safe space to stretch.

“Many of us find ourselves drinking a lot of water because of the extreme heat as we travel to the North.Yet along the way, there are no safe eateries where passengers can rest or refresh themselves. Sometimes the heat forces them to buy more water at inflated prices, even when they are already stretched thin financially. What can we do as drivers? “ Kimani says.

Along the Marsabit–Isiolo road, 20-year-old commuter Cyprian Nabea recalls nights when travel turned into terror.

“In 2021, I went through one of the darkest moments of my life when armed carjackers stopped my bus at Moyale. They opened fire, shooting at us three times. By God’s grace, none of my passengers were injured, but the memory of that night still haunts me because I lost a colleague in a similar attack,” he says.

The punctures on the lonely stretch of road have left passengers stranded in unsafe spots, and the only hope of safety lies in parking near police barriers.

“We don’t necessarily need escorts, but what we truly need is just one well-established police centre along this stretch. It takes about three hours from Isiolo to Maralal, yet you cannot use these roads freely because of the constant threat of bandits. Even when police are deployed, they are often intimidated and eventually withdraw, leaving us exposed once again,” Nabea says.

Further north in Isiolo, Abdi Salan, a youth coordinator, sees the problem as part of a bigger story of marginalisation.

“Security is a big issue. There is no place to relieve ourselves. During accidents, responses are slow and hospitals are very far. With these amenities, we will travel well and safe,” Salan notes.

Residents like Husain Ibrahim have welcomed the tarmacking of the Isiolo–Marsabit road, which has cut travel time and boosted trade. Yet, he contends that tarmac alone is not enough.

“We are happy the road is tarmacked. But we also need places to stop, rest, and be safe,” he emphasises.

Kenya’s problem is not lack of roads. Over the past decade, the government has invested heavily in expanding the network, which now stretches more than 239,000 kilometres.

National trunk roads cover about 57,000 kilometres, linking major towns and facilitating trade. Counties manage the rest. Yet despite this impressive growth, nearly 48 per cent in eight years, amenities have lagged far behind.

The consequences are evident in the grim statistics of road accidents. Each year, Kenya records more than 4,600 road deaths, with thousands more left injured.

The National Transport and Safety Authority (NTSA) estimates that fatigue is a significant factor in these accidents, particularly for long-distance drivers. Without rest areas, truckers and matatu drivers are forced to push beyond safe limits, increasing the risk of crashes.

The economic cost is equally staggering, an estimated Sh450 billion annually, or about five per cent of the GDP, is lost to road accidents and inefficiencies, according to statistics from the Ministry of Transport. The brunt of this burden falls disproportionately on trauma victims and their families while hospitals and emergency services also bear the strain.

In a bid to address the devastating toll of road accidents, NTSA recently launched the National Road Safety Action Plan 2024-2028. The initiative aims to curtail the alarming rate of road carnage, which not only shatter families but also pose a significant economic burden on the nation.

Bus driver Patrick Otieno, who plies the Nairobi–Kisumu route weekly, laments the absence of structured stops, especially after Nakuru.

“The children cry in the bus, but what can you do? If you stop by the roadside, you risk being robbed, and if you push on, the passengers complain. It is like being trapped,” he laments.

For him, the fatigue of navigating winding escarpments, sharp corners, and steep descents without a proper rest bay is not just stressful, It is dangerous.

“There are times when I feel like parking just to rest my eyes, but where do you park? The shoulders are narrow, and lorries speed past. One mistake, and you cause a pile-up. These roads are busy with sugarcane trucks, fuel tankers, and buses. Without rest areas, it’s a ticking time bomb,” he says.

For his passengers, the lack of facilities along the Nairobi–Kisumu stretch means traveling under constant discomfort. Families with young children are forced to improvise in humiliating ways, while expectant mothers endure journeys with no guarantee of safe sanitation. It is a daily reminder that roads alone do not make travel dignified.

On the Nairobi–Mombasa highway, the story is equally troubling but with its own unique twist. Truck driver Salim Ali, who ferries containers from Mombasa Port to Nairobi, says the absence of safe truck parks has turned the corridor into a nightmare.

“Sometimes we are forced to park by the roadside because of fatigue or curfew restrictions. That is when thugs strike. They open the trailers, steal goods, and sometimes even attack drivers. A proper resting park would solve this, but the government has been promising for years,” Ali narrates.

For those travelling to the Coast, the journey to Mombasa is long and exhausting. But the problem is not just about personal fatigue. The Nairobi–Mombasa corridor carries about 95 per cent of Kenya’s cargo traffic. Any disruption on the road due to accidents or crime has ripple effects across the region’s economy.

“Every other country along this corridor is building rest areas and truck parks. Yet here in Kenya, the busiest road in the country has no safe, structured parking bays for trucks,” he says.

According to Ali, the drivers and other road users normally face wild animal attacks past Mutitu Andei, especially at night when elephants and buffalos cross the road or linger near parked trucks. Many drivers have been attacked along the stretch.

“Sometimes a vehicle breaks down or fatigue forces you to stop, and before you know it, animals surround you. It is terrifying because without proper rest bays, we are exposed to dangers we cannot control,” he adds.

Globally, the situation is handled very differently. In South Africa, highway rest stops are spaced every 50 to 80 kilometres, equipped with fueling stations, eateries, restrooms, and emergency services.

In India, where long-distance trucking is critical to the economy, the government has rolled out a programme of “Highway Wayside Amenities,” with over 600 identified sites to be developed with toilets, fuel stations, dormitories for drivers, and medical clinics.

The United States and Europe go even further, with rest areas planned into every new road project, ensuring that no traveler is more than a 30-minute drive from a safe, regulated stop.

By contrast, Kenya’s approach has treated amenities as an afterthought. A motorist driving from Nairobi to Mombasa, a journey of nearly 500 kilometres, will find no structured rest areas, except petrol stations and roadside kiosks.

Truck drivers hauling freight to Uganda, Rwanda, or Ethiopia face similar challenges, sleeping in their vehicles or parking dangerously on road shoulders. This gap leaves Kenya out of step with global best practices, undermining both safety and competitiveness.

Found champion

Beyond accidents, the lack of amenities raises public health concerns. Travelers often resort to using the bush, contaminating the environment and risking outbreaks of waterborne diseases.

Informal eateries springing up along highways, unregulated and unsupervised, expose travelers to food poisoning. In regions far from hospitals, accident victims face delayed responses, often with fatal consequences.

Despite these realities, the issue has remained neglected in policy debates for years. Roads are built and launched with pomp, but supporting amenities are dismissed as a second thought.

In the Senate, however, the issue has finally found a champion. Nyeri Senator Wahome Wamatinga has tabled a motion calling for the creation of social amenities along major highways.

His proposal seeks to compel national and county governments, in collaboration with agencies such as the Kenya National Highways Authority (KeNHA), to develop designated facilities that include washrooms, resting bays, eateries, medical emergency points, and secure parking.

Wamatinga argues that these are not luxuries but necessities for a country that aspires to modern infrastructure standards.

“Our highways are the backbone of the economy, but we cannot continue to ignore the welfare of those who use them. This is about protecting lives, enhancing dignity, and ensuring that road travel in Kenya meets modern standards,” he said.

The proposal emphasizes the need for a multi-pronged strategy that encompasses a unified policy framework involving key ministries and agencies, a thorough needs assessment to map out priority areas, and the promotion of Public-Private Partnerships to attract investment.

“It further calls for the utilisation of road reserves to establish critical services such as satellite clinics, ambulance stations, and fire trucks, ensuring that travelers, particularly children, the elderly, and the sick, have access to essential support during long-distance journeys,” says Wamatinga.