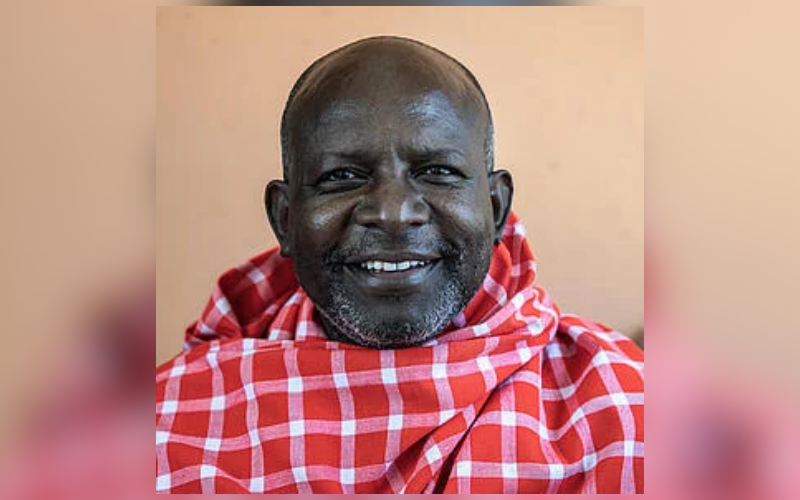

I have met Mali ole Kaunga in many places, in conference halls heavy with policy language, open plains traced by camel caravans, and community forums where elders speak softly but with authority. Each time, one thing stands out: he is never in a hurry.

“You don’t rush land. If you rush it, you lose it,” he once told me.

That sentence has stayed with me, perhaps because it explains not just his work, but his way of being.

Over the years, I have watched Mali ole Kaunga return to the same conversations without fatigue. At land summits, he remembers names; along caravan routes, he remembers places; in policy spaces, he remembers promises made years earlier.

“This work is about memory, and if you forget where you came from, land will remind you, sometimes painfully,” he told me during this year’s 5th edition of the Community Land Summit (CLS).

What strikes me most is how often people seek him out, not for headlines, but for grounding. Elders pull him aside. Young activists ask for guidance. Donors ask careful questions. He listens to all of them with the same attentiveness.

In a space often crowded with urgency, he offers steadiness.

A journey that began long before recognition

Long before community land rights entered mainstream policy conversations, Kaunga was already walking this path. His journey toward land justice began in 1994, shaped by lived experience as a Laikipia Maasai and by watching communities slowly pushed out of spaces they had occupied for generations.

“At the time, people didn’t call it land injustice, though we were already feeling its effects, displacement, conflict, loss of identity,” he reflects.

What began as community advocacy grew into OSILIGI, meaning hope. OSILIGI later evolved into IMPACT Kenya, an organisation that today stands at the centre of Indigenous land rights advocacy in Kenya and the region.

Yet Kaunga is quick to point out that this work has never been about building institutions for their own sake.

“It was about responding to what communities were asking for: protection, recognition, dignity.”

Holding space, not the spotlight

At the Community Land Summit, you can often tell who belongs to this work by how they move through the room. Some speak in policy language; others speak in stories.

Mali ole Kaunga speaks in pauses.

He lets elders finish their thoughts. He allows youth to challenge respectfully.

He does not rush into disagreement. When tension rises, as it often does when land is discussed, he reminds participants why they are there.

“Land discussions are emotional because land holds grief, and if we ignore that, we cannot resolve anything,” he says quietly.

The Summit, now in its fifth year, has grown not because it promises easy answers, but because it acknowledges complexity.

Watching Kaunga convene a forum is an exercise in restraint. He speaks, yes, but more importantly, he listens. Voices from Samburu, Isiolo, Marsabit, Laikipia, the Coast and beyond, including Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan and Ethiopia, fill the room.

“My role is not to speak for communities, but to create space for them to speak for themselves,” he explains.

That philosophy has shaped the Summit into one of the most respected platforms for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs), where elders sit alongside youth, women challenge inherited exclusions, and policymakers are asked to listen before responding.

“Leadership is not about holding the microphone, but about holding the space steady,” Kaunga insists.

Land justice, he believes, is not won through declarations or deadlines. It is built slowly, through trust, patience and presence.

“Land teaches patience, and patience teaches justice,” he says.

As I watch him move from one forum to another, still listening more than he speaks, I am reminded that some roads are not meant to be rushed. They are meant to be walked.

Land is never neutral

In many development conversations, land is reduced to numbers, acreage, value, and potential return. Kaunga resists this framing. Community land, he argues, is not empty, and it is never neutral.

He tells me about communities that finally received communal land titles after decades of uncertainty, and the relief that followed.

“For some elders, it meant they could finally sleep, because they knew their grandchildren would not be strangers on their own land,” he says.

Yet he cautions that titles alone are not enough.

“Registration without governance can create new conflicts. That is why we invest so much in capacity, building, helping communities manage land together, transparently.”

It is slow work, often invisible, but essential.

For communities, land carries memory, culture, livelihoods and future security. When it is taken, fragmented or commodified without consent, the damage goes far beyond economics.

This belief underpins IMPACT’s long-standing insistence on Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), not as a box-ticking exercise, but as a lived process.

“Consent is not a signature collected at the end. It must allow communities time, information, and the real freedom to say no,” he says.

Perhaps no initiative captures this philosophy better than the Camel Caravan, now in its 14th year, which Kaunga founded more than a decade ago. Moving across ancestral routes, the caravan brings dialogue on land, peace, climate and culture, reminding participants that advocacy does not always happen in boardrooms.

“Sometimes you have to walk the land to understand it,” he says.

The caravan, like the Summit, endures because it is trusted by communities who see their realities reflected, and by donors who recognise consistency, accountability and impact over decades.

Why symbolism matters

The Camel Caravan may appear symbolic, but symbolism matters deeply in Indigenous spaces.

“Walking ancestral routes is a reminder that land is lived,” Kaunga says. “You cannot understand it from documents alone.”

Over fourteen years, the caravan has become a mobile classroom where policy meets pastoralism, and dialogue replaces confrontation.

“Peace is not negotiated only at tables,” he adds. “Sometimes it is negotiated on the road.”

In recent conversations, Kaunga speaks openly about transition.

“I won’t be in active administration forever, and that is okay with me,” he says without hesitation.

What matters to him now is mentorship, particularly of Gen Z and emerging Indigenous leaders.

“The future of land justice cannot rest on one generation. We must prepare those who will carry this work further than we did.”

As he speaks about stepping back, there is no sense of unfinished business, only continuity.

“If this work depends on me, then I have failed. Success is when the work continues without you,” he says.

In a world that celebrates speed, Mali ole Kaunga has chosen endurance. In a time that rewards noise, he has chosen consistency.

Land justice and conservation are not a campaign. It is a long road. And some of the most important journeys are walked, not announced.